Peck’s Addition: The Intentional Destruction of an Urban Appalachian Neighborhood

- appalachianplaces

- Jan 17, 2022

- 7 min read

Updated: Jan 28, 2022

By Phillip J. Obermiller

Because people live in a settled neighborhood doesn’t mean they can remain peaceably in their homes, as rural Appalachians living near mountaintop removal or fracking sites can testify. In urban areas authorities often invoke the right of eminent domain to repurpose entire neighborhoods for a public use such as a stadium, a highway, or a park.

A more insidious strategy municipalities use to obtain property is to hasten the deterioration of neighborhoods by withholding public services or putting a landfill or sewage treatment plant in the target area. This method is slower and less confrontational than using eminent domain, but effectively encourages residents to sell out at reduced prices and move away.

Low-income and minority neighborhoods are particularly susceptible to these manipulations which are routinely used to justify “urban renewal” and “slum clearance” schemes. The intentional destruction of neighborhoods across North America has been going on for well over a century and continues to this day. Urban Appalachians are not immune to these depredations.

Located in Hamilton, Ohio, Peck’s Addition was a port-of-entry neighborhood for Appalachian migrants throughout the early-to-mid 20th century. Pushed by the mechanization of mining and farming, along with job competition caused by a rapidly growing rural population, Appalachians sought work in industrialized cities like Hamilton. Port-of-entry neighborhoods offered newcomers inexpensive housing, access to local factories, and a place to be certain of employment before making longer-term plans.

Along with the Mosler Safe Company, and later a Fisher Body plant, it was Champion Paper that drew workers to Hamilton. Less than 40 years after its founding in 1893, Champion had some 4,000 employees. The company frequently sent buses and recruiters into the mountains to attract unskilled and semi-skilled workers to its rapidly expanding labor force. In some parts of eastern Kentucky the phrase “I’m going to Champion” meant migration to Ohio, and the common word for a suitcase was a “Hamilton.”

Champion appeared to swap land for labor in the 1930s when it sold 90,000 acres of forested property to the federal government for the creation of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The company went into decline following World War II and closed its Hamilton factory in the spring of 2012. In some ways Peck’s Addition followed the company’s trajectory.

In the late 1800s Dr. John Peck began assembling parcels of land alongside the Great Miami River into a 230-acre site to sell as individual building lots. The area became known to some as Peck’s Addition after it was annexed by the city of Hamilton in 1908. To others it was “The Bottoms” because the land was not only adjacent to but often in the Great Miami River. About half of it was swampland called Big Pond during the 1800s because it rarely dried out between the eight major floods of that era.

Following a disastrous flood in 1913, Peck’s Addition became less prone to flooding when the Miami Conservancy District constructed five dams and 43 miles of levees. The chief engineer on that project was Arthur E. Morgan who would go on to become the first chairperson of the Tennessee Valley Authority. Ironically, Morgan, who made the Addition safer for its urban Appalachian residents, would go on to inundate neighborhoods and entire towns in the Appalachian region by building dams across many of its rivers.

Over time, low-cost housing developed in Peck’s Addition ranging from early shacks made of scrap metal and wood to some fairly nice homes. Although some 120 houses were lost in the 1913 flood, there were about 400 houses in the Addition by the early 1940s, sheltering perhaps 2,000 residents. A high rate of population turnover characterized the Addition in the 1940s when newcomers arrived for jobs in the local WW II defense industries, and longer-term residents moved on to working-class neighborhoods near Hamilton such as the Belmont District, Fairfield Township, Gobbler’s Knob, and Happy Top.

Not everybody viewed the neighborhood favorably, however. From the early 1900s political and business leaders in Hamilton considered Peck’s Addition as unsuitable for human habitation; this pejorative attitude infected their thinking about the homes and the people living there. Civic leaders came to believe the area was appropriate only for development as a public park. Even though plans for such a park were repeatedly commissioned and voted on, they were never funded.

Although the neighborhood’s residents were taxpayers, they were refused basic public services such as water and sewer lines, fire hydrants, and paved streets. One observer put it succinctly: “Hamilton had 30 miles of sewers, 12 miles of paved roads, 527 street lamps, 425 fire plugs, and 25 miles of water pipes. None of them had been installed in Peck’s Addition … (because it) was going to be a park. It didn’t need the services.”

In the early 1960s the city began withholding building permits for homes in the Addition, which meant that no roofing or siding replacements or other basic repairs were allowed. After artificially depressing home values by withholding public utilities and permits for improvements, the city began a process of buying out homeowners at steeply discounted prices.

Another factor contributing to the decline of the neighborhood was the city’s 1938 decision to open a dump on land it had acquired in the Addition. Residents were subjected to rat infestations, obnoxious odors, and dense sulfurous smoke when the dump caught fire, often smoldering for days and covering the neighborhood in soot. The dump eventually became a covered landfill, but not before city workers hauled off 150 truckloads of festering trash in 1979 so plans for “developing” the area could proceed.

Despite the obstacles imposed by the city, residents of the Addition were resourceful and resistant. A homeowner, cited for “unsanitary conditions” because she was running a herd of hogs on the dump, pointed out to the judge that the dump itself was an unsanitary activity run by the city. A family prospered by operating a junkyard on their property. When the city objected that it violated zoning regulations, the operator pointed out to the court that there was no prior record of Hamilton enforcing zoning codes in the Addition. Other residents took advantage of the overgrown vacant lots created by city buyouts to clear them for gardens and sell the produce at roadside stands.

Many owners ignored the bans on home improvements by doing the work themselves in the evenings and on weekends when city inspectors were off duty. One enterprising family specialized in digging septic systems or providing outhouses, most of which were constructed at night. Another family scavenged the dump for usable items, making a modest income from selling firewood, second-hand clothing, and used furniture.

Life in the Addition was arduous, in part because of the harsh strictures the city placed on it. Data collected by researchers in the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s show it had its fair share of crime, truancy, delinquency, poverty, and welfare dependency, but not excessively greater than in comparable neighborhoods. When asked about crime in the Addition, a Hamilton police officer noted, with tongue firmly in cheek, that having Kentuckians on his beat made a difference: “Yes, they do have an effect. On holidays and weekends they go home and we sit around and play cards.”

Over time Peck’s Addition transitioned from a port-of-entry neighborhood to one with long-term homeowners. One resident in particular, Tom Stephens, became a fierce advocate for the neighborhood. He confronted city officials, commission members, and federal bureaucrats in their offices and during public meetings. He pointed to “a conspiracy by a gang of political ward-heelers to wrest some very valuable property in the middle of the city from its rightful owners.” In carefully documented letters, he demanded the resignations of some office holders. Failing that, he challenged them to public debates “in the center of Hamilton…the center of Hamilton, as you are aware is in Peck’s Addition.” Stephens’ efforts were unsuccessful in the face of an intransigent municipal government. In frustration, he began campaigning in 1979 for the Addition to secede from the city and become its own jurisdiction, again to no avail.

Although the concepts of redlining (withholding private and public investment from neighborhoods based on their demographics) and gentrification (displacement of low-income and working-class residents from their communities) were not clearly articulated until the 1960s, it is clear that Peck’s Addition was the focus of municipal gentrification and redlining efforts almost from the time of its annexation. How did this happen?

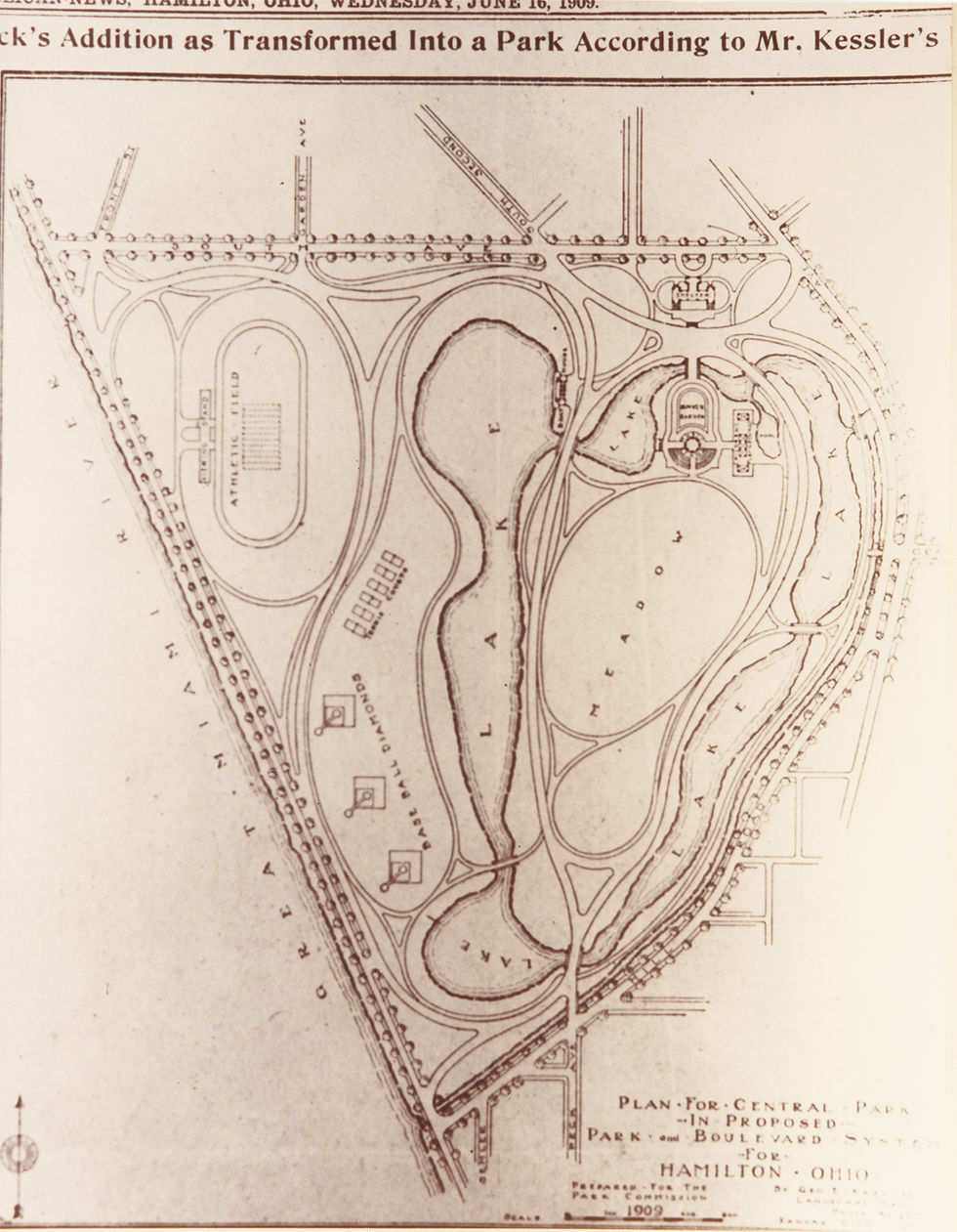

In the early 1900s a member of the Hamilton Park Commission, S.D. Fitton (John Peck’s brother-in-law), invited landscape architect George Kessler to design a system of public parks featuring the Addition as its crown jewel. This approach was grounded in the City Beautiful Movement then fashionable among upper-middle class people who believed aesthetic endeavors (i. e. creating parks and erecting monuments) would ease social problems.

Noted urbanist Jane Jacobs dismissed the movement as an “architectural design cult” that ignored the benefits of neighborhood life, especially among the poor. Nevertheless, politicians and administrators in Hamilton embraced City Beautiful tenets based in part on their ethnic and class differences from the people in Peck’s Addition. The German and Italian burghers who ran the city lived in their own well-established enclaves, socialized with each other, and benefitted from the wealth generated by Champion and other companies. Research done through Miami University indicates the Appalachian newcomers were typical of most first-generation migrants in keeping to their own neighborhoods and working-class social circles. It would take a few generations for Appalachians to gain political traction in Hamilton. Meanwhile, city officials continued to ignore neighborhood residents’ grievances while promoting plans for their removal.

The city’s appalling strategy of disinvestment worked. In 1977 there were about 60 residents living in 23 homes in the Addition. By 1981, 12 families were left. Once the remaining families and individuals had been run off, bought out, or died, the city fulfilled its long-held intentions. Peck’s Addition no longer exists, its homes demolished to create a space for Hamilton’s University Commerce Park. The former Addition is now the site of the 55-acre Vora Technical Park and the Hamilton campus of Miami University. In a final act of erasure, Peck Boulevard which ran through the middle of the former neighborhood, was renamed University Boulevard. Although the neighborhood has been physically obliterated, it still has a virtual life — its residents are remembered by over 1,000 members in the Peck’s Addition Facebook group, where memories of friendships and hardships are shared.

Some might argue that the commerce park is a “higher and better” use of the place where this urban Appalachian neighborhood once stood, but that does not excuse the shameful way the goal was achieved. Helen Hubbard, one of the last residents of the Addition, summed up her experience concisely in the WLWT documentary, A Secret Shame: The Forgotten People of Peck’s Addition, when she said, “They think we ain’t no people.”

Phillip Obermiller is a senior visiting scholar in the School of Planning at the University of Cincinnati and a fellow at the University of Kentucky Appalachian Center.

For further reading:

Maloney and Obermiller, “Urban Appalachia” section editors, Encyclopedia of Appalachia. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006.

Obermiller, “Migration,” in Richard Straw and H. Tyler Blethen, eds., High Mountains Rising: Appalachia in Time and Place. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Comments